Sometimes a single reference in an old newspaper underscores how very different the mindset of an earlier time was from that of our own time.

"Lost from the subscriber, living on Raccoon

Creek, in Woolwich township, Gloucester county, West New-Jersey, on the night

between the 9th and 10th of this instant October, an

indented female child; her name is Polly Murphy, very near five years of age,

pretty tall for her age, of a fair complexion, has ruddy cheeks, grey eyes,

light hair, and a small scar on her forehead; had on an almost new homespun

lincey petticoat, with red, brown and yellow stripes, turned up round-about, a

red ragged woolen short gown, and a coarse ozenbrigs shift...¹ "

As a parent reading this notice from 1775, my heart went out instinctively to that lost child, remembering a cold November when my not yet three-year-old daughter went out into the night in her stocking feet - having decided to follow her mother's car to the library - and the panic I felt until she was found, safe, but half a mile away. My sympathy is naturally with the parents of Polly Murphy, but they were not out looking for their child. Her master was.

"...It is supposed she has been taken away by her

parents, who stayed that night with the subscriber, and with the child

disappeared that morning. The father’s

name is Henry Scharff, has a lean face and thin hair, had on an old, worn out

blue coat; the mother is a lusty, hearty woman, of a fair complexion, has big

lips, and black hair, and is big with child.

Whoever takes up the above persons with the above described child, and

secures them, so that the subscribers may have the child again, and the parents

convicted of the theft, shall have five pounds reward, or for the child alone

three pounds, and all reasonable charges paid by ANDREW MINTZ"

[Pennsylvania Gazette October 18, 1775]

18th Century America's cultural and class distinctions are stark in this run-away advertisement. From Mintz's perspective, the poor white parents of Polly Murphy have taken advantage of his hospitality and broken a binding contract by removing their five-year-old daughter from her indenture. Readers of the newspaper would be expected to view the father, with his different surname, and the pregnant, probably Irish mother, as dishonest as well as unfit parents from a societal underclass.

Hard information about Andrew Mintz is very hard to come by. This single newpaper ad from 1775 is all that I have been able to

find . Intriguingly, Mintz is an Ashkenazic or eastern

European Jewish surname. Sephardic or "Spanish" Jews were more common

in 18th Century America than the Ashkenazim, though there were a few of

these. He could have converted to Christianity, as did my ancestor

Eleazer Cohen, a merchant from Amsterdam who lived in Philadelphia at

this time.

More likely Mintz could just be a German name like Müntz that happened to be spelled like a Jewish one. There was a Benedict Müntz

who died in Philadelphia in 1764 whose name was also spelled Mintz.

These Mintz's were not Jewish, and intermarried with Moravians.

Sometimes even very young children like Polly Murphy were bound to service when their families could not afford to support them. These indentures were long, and did not include niceties such as the option for early termination if the circumstances of the parents improved. They had no recourse if they just wanted her home again. Their child became chattel.

This was a common condition in 18th Century America, a form of long-term white slavery at a time when the permanent enslavement of black people was well established. Appallingly, it is also a form of slavery that exists in different but still recognizable forms today, with bonded debt slavery and child labor affecting millions of people around the world.

________________________________________________________________________

1. Documents Relating to the Colonial History of the State of New Jersey, First Series --Vol. XXXI

Extracts from American Newspapers Relating to New Jersey for the Year 1775, Edited by A. Van Doren Hon Eyman, Somerville, N.J. : The Unionist-Gazette Association, Printers, 1923.

Tuesday, March 31, 2015

Thursday, March 26, 2015

Button, Button, Who's Got the Wooden Buttons?

It is difficult for an historian to generalize about the folkways of colonial New Jersey, with its two Provinces, East and West, and distinct populations of Dutch, German, Swedish, English, Scottish, Irish, African and Native American origins. Add to that the Quaker influence in West New Jersey, and divided Dutch Reformed congregations in East, and the overall demographic impression in the years leading up to the American Revolution is of a remarkably heterogeneous society with sub-regional characteristics and a solid middle class.

There is the odd reference in a traveler's letter to respectable Jersey women who sewed in their shifts.1

Whenever I do come across a contemporary reference that seems to make a general claim about colonial New Jersey's material culture, I look for evidence to substantiate or refute it. Consider this fascinating newspaper advertizement from 1770:

Benjamin Randolph

takes this method to inform his customers, and the public

in general, That he has for sale, at his ware room of

carving and cabinet work &c., at the Sign of the Golden Eagle,

in Chestnut-street, a quantity of Wooden buttons, of various

sorts, and intends, if encouraged, to keep a general

assortment of them...The people of New-Jersey (in general)

wear no other kind of buttons, and say they are the best and

cheapest, can be bought, both for strength and beauty, and

he doubts not that they will soon recommend themselves to

the public in general.

[The Pennsylvania Gazette Jan. 18, 1770]

Mr. Randolph was born to a Quaker family in Monmouth County, New Jersey and had set up business in Philadelphia. He seems to be pitching his buttons to the West-New Jersey market, or perhaps also to customers in Philadelphia with a cultural or religious affinity for those on the far shore of the Delaware. Another ad that year reportedly described his desire to purchase "apple, holly and laurel wood, hard and clear-grained" for button manufacture.

Was he right that "The people of New-Jersey (in general) wear no other kind of buttons", or was he inflating their generality to build a new customer base, and perhaps also to appeal to domestic purchasing impulses while many British goods, including gold and silver buttons, were subject to non-importation embargo?

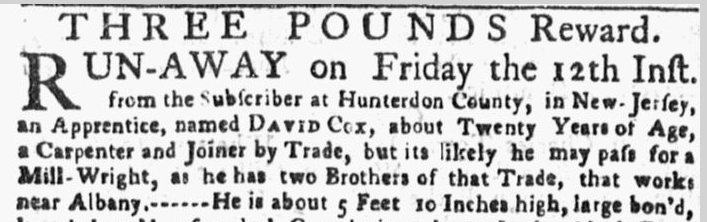

One place to look for verification of the wooden button claim would be those New Jersey runaway descriptions in contemporary newspapers (albeit that until 1778 all of these were published outside New Jersey). At least for the lower third of society, these notices of absconded apprentices, prisoners, servants and slaves should provide a useful way to compare button descriptions for evidence of any discernible trends.

As it happens, I can run that analysis, for I have been compiling a database that currently has 627 individual male New Jersey runaways with clothing descriptions between the years 1767 and 1782. My sources are those colonial and revolutionary-era newspapers from which extracts were transcribed and published in multiple volumes of the New Jersey Archives between the late 1880s and the First World War. The volume that covers late 1774 through 1775 contains incomplete transcriptions and substitutes ellipses for clothing descriptions for all but nine runaway notices, but the other years appear to be faithful and comprehensive reproductions of the 18th century text.

There are 142 button descriptions among the clothes worn by these 627 men that offer insight into the materials from which there were made. Five of these are military uniform buttons (one worn by an escaped slave), leaving 137 that could conceivably represent lower class clothing worn in New Jersey during this time.

Buttons (sometimes their notable absence) are only described for visible outer clothing - surtouts, coats, jackets and breeches. These runaway notices tell us virtually nothing about shirt buttons, most commonly made of thread. It is possible that only those articles of clothing that were clearly seen and well known to the subscriber were described right down to the buttons. It is also possible that only buttons considered unusual or distinctive were included in the descriptions. It is prudent to bear these alternative hypotheses and qualifications in mind as we examine the evidence.

Among these 137 button descriptions, I find 15 that are wooden buttons, including one fellow who wore a suit of clothes with wooden buttons on both the coat and jacket. I also find 25 simply described as metal, and another 28 that were either white metal or pewter. There were mohair or thread basket buttons (13 and 6, respectively, although some of the latter may have been metal), as well as 10 brass and 8 more of yellow metal. There were 9 references to horn, and 8 to covered buttons, though the latter could be under represented as most of these were the same color fabric as the clothing and might not have been readily discernible. There are handful of other types of button mentioned with low representation (bone, tortoiseshell, glass, composite materials, gilt) and even one described as "Philadelphia buttons", made by one of the two local manufacturers of metal buttons in that City.

Wooden buttons, it seems, were worn by these New Jersey runaways slightly more than some other common types but considerably less than white metal. Even if we sorted these 15 references to wooden buttons by East and West New Jersey and compared them to other button types found on runaways from these places, it is unlikely that there would be a strong enough correlation to back up Mr. Randolph's claim of general use. One could further speculate that wooden buttons could have been favored by some rural Quakers in plain dress, but simple white metal cloth covered buttons were also available to them.

The most interesting conclusion from the New Jersey Runaway descriptions is not that wooden buttons were the norm, but that nearly two dozen different types of civilian button were described, some in sufficient quantities to be considered something more than rare occurrences. Noting once again that cloth covered buttons may be under counted in these descriptions, there is much to suggest that white metal, mohair, brass, and, yes, wooden buttons were regularly worn by the lower classes in New Jersey at this time. Perhaps the market was not as great as Mr. Randolph imagined or hoped might come to be, but there was a market nonetheless.

Benjamin Randolph went on to serve in the First Philadelphia City Troop of horse at Trenton and Princeton in 1777, but today he is better known as a talented colonial furniture and cabinet maker. Thomas Jefferson's writing desk - the one on which he drafted the Declaration of Independence - is thought to have been made in May, 1776, by Benjamin Randolph.

________________________1. De Pauw, Linda Grant, Fortunes of War: New Jersey Women and the American Revolution (Trenton, NJ, 1975).

There is the odd reference in a traveler's letter to respectable Jersey women who sewed in their shifts.1

Cyder spirits such as "Jersey Lightning" or Apple Jack would be a strong candidate for the regional alcoholic beverage of the era. Still, there is not much else that would support an endemic material culture in colonial New Jersey in the 1770s distinct from that of the wider Delaware Valley in the West, or New York and the Hudson Valley in the East. Fully half the breeches described in New Jersey runaway notices in period newspapers were made of leather, but this was a common working class garment in other colonies. Short gowns may have been more common in the Middle Colonies than in the Eastern ones, but not just in New Jersey.

Whenever I do come across a contemporary reference that seems to make a general claim about colonial New Jersey's material culture, I look for evidence to substantiate or refute it. Consider this fascinating newspaper advertizement from 1770:

Benjamin Randolph

takes this method to inform his customers, and the public

in general, That he has for sale, at his ware room of

carving and cabinet work &c., at the Sign of the Golden Eagle,

in Chestnut-street, a quantity of Wooden buttons, of various

sorts, and intends, if encouraged, to keep a general

assortment of them...The people of New-Jersey (in general)

wear no other kind of buttons, and say they are the best and

cheapest, can be bought, both for strength and beauty, and

he doubts not that they will soon recommend themselves to

the public in general.

[The Pennsylvania Gazette Jan. 18, 1770]

|

| Benjamin Randolph by Charles Willson Peale (Philadelphia Museum of Art) |

Was he right that "The people of New-Jersey (in general) wear no other kind of buttons", or was he inflating their generality to build a new customer base, and perhaps also to appeal to domestic purchasing impulses while many British goods, including gold and silver buttons, were subject to non-importation embargo?

One place to look for verification of the wooden button claim would be those New Jersey runaway descriptions in contemporary newspapers (albeit that until 1778 all of these were published outside New Jersey). At least for the lower third of society, these notices of absconded apprentices, prisoners, servants and slaves should provide a useful way to compare button descriptions for evidence of any discernible trends.

As it happens, I can run that analysis, for I have been compiling a database that currently has 627 individual male New Jersey runaways with clothing descriptions between the years 1767 and 1782. My sources are those colonial and revolutionary-era newspapers from which extracts were transcribed and published in multiple volumes of the New Jersey Archives between the late 1880s and the First World War. The volume that covers late 1774 through 1775 contains incomplete transcriptions and substitutes ellipses for clothing descriptions for all but nine runaway notices, but the other years appear to be faithful and comprehensive reproductions of the 18th century text.

There are 142 button descriptions among the clothes worn by these 627 men that offer insight into the materials from which there were made. Five of these are military uniform buttons (one worn by an escaped slave), leaving 137 that could conceivably represent lower class clothing worn in New Jersey during this time.

Buttons (sometimes their notable absence) are only described for visible outer clothing - surtouts, coats, jackets and breeches. These runaway notices tell us virtually nothing about shirt buttons, most commonly made of thread. It is possible that only those articles of clothing that were clearly seen and well known to the subscriber were described right down to the buttons. It is also possible that only buttons considered unusual or distinctive were included in the descriptions. It is prudent to bear these alternative hypotheses and qualifications in mind as we examine the evidence.

Among these 137 button descriptions, I find 15 that are wooden buttons, including one fellow who wore a suit of clothes with wooden buttons on both the coat and jacket. I also find 25 simply described as metal, and another 28 that were either white metal or pewter. There were mohair or thread basket buttons (13 and 6, respectively, although some of the latter may have been metal), as well as 10 brass and 8 more of yellow metal. There were 9 references to horn, and 8 to covered buttons, though the latter could be under represented as most of these were the same color fabric as the clothing and might not have been readily discernible. There are handful of other types of button mentioned with low representation (bone, tortoiseshell, glass, composite materials, gilt) and even one described as "Philadelphia buttons", made by one of the two local manufacturers of metal buttons in that City.

Wooden buttons, it seems, were worn by these New Jersey runaways slightly more than some other common types but considerably less than white metal. Even if we sorted these 15 references to wooden buttons by East and West New Jersey and compared them to other button types found on runaways from these places, it is unlikely that there would be a strong enough correlation to back up Mr. Randolph's claim of general use. One could further speculate that wooden buttons could have been favored by some rural Quakers in plain dress, but simple white metal cloth covered buttons were also available to them.

The most interesting conclusion from the New Jersey Runaway descriptions is not that wooden buttons were the norm, but that nearly two dozen different types of civilian button were described, some in sufficient quantities to be considered something more than rare occurrences. Noting once again that cloth covered buttons may be under counted in these descriptions, there is much to suggest that white metal, mohair, brass, and, yes, wooden buttons were regularly worn by the lower classes in New Jersey at this time. Perhaps the market was not as great as Mr. Randolph imagined or hoped might come to be, but there was a market nonetheless.

Benjamin Randolph went on to serve in the First Philadelphia City Troop of horse at Trenton and Princeton in 1777, but today he is better known as a talented colonial furniture and cabinet maker. Thomas Jefferson's writing desk - the one on which he drafted the Declaration of Independence - is thought to have been made in May, 1776, by Benjamin Randolph.

________________________1. De Pauw, Linda Grant, Fortunes of War: New Jersey Women and the American Revolution (Trenton, NJ, 1975).

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)